Author photo: Graveyard at St. Andrew's, Moretonhampstead, UK Author photo: Graveyard at St. Andrew's, Moretonhampstead, UK Most people know the dictionary definition: To consecrate is to make sacred. The root is the Latin sacer meaning “sacred.” The prefix con- can mean either “with” or “thoroughly, completely, intensely.” And so, consecration denotes a total dedication of something or someone to the sacred. For my novel in stories, Consecration Pond, I chose as epigraph a few lines from Howard Nemerov’s poem “The Pond.” It’s a five-page poem, and in my view, a masterpiece. Early in the poem, Nemerov describes the death of a boy who went skating on the pond the previous winter and drowned. He tells us that residents of the town where the pond is located have decided to name the pond for the boy: Christopher Pond. Later in the poem, Nemerov refers to this death as an “accidental consecration.” In “Spring Ice,” the ninth story in Consecration Pond, the narrator refers to Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, which, like Nemerov’s poem, speaks of death as consecration: "But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract." (November 19, 1863) Reflecting on this passage, it’s worth noting that more than 3,100 Union soldiers died at Gettysburg. But is death, whether accidental or sacrificial, the only means of consecration? Can we, the living, somehow transform our own experiences—of trauma, shame, loss—into something sacred? If so, how? I think the answer begins with that three-letter prefix con-, which communicates a thorough and intentional dedication to the work of making sacred. But something else is needed first: Before we can begin the work of dedication, we must acquiesce to the circumstances that compel it. In Nemerov’s poem, the residents of the town acquiesce to an event they are powerless to change—the death of a child—by giving the pond the child’s name. Nemerov explains unambiguously that this naming reflects “Not consolation, but our acquiescence.” Similarly, Lincoln forces his listeners to acknowledge the deaths of those 3,100 Union soldiers as prelude to the act of dedication: “We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live.” In Consecration Pond, a similar two-part act of acquiescence and dedication enables many of the narrators to consecrate experiences in their own lives. For example, in the opening story, “Prayer of the Bell,” Lucy—a stargazer—experiences a violation. She initially tries to hide from the experience—locking her doors and pulling down her window shades. But while listening to her neighbor’s bell, she allows herself to let the experience go—in short, she acquiesces to a past she cannot change. Then, with her neighbor’s help, she consecrates the experience with a ritual burial, marking the burial place with a star. In contrast, some characters in Consecration Pond cannot achieve this sacred acquiescence. Their attachment to their loss—and its attendant regret, guilt, or grief—keeps them frozen in the past. In the words of Father Mackenzie in the eighth story, “Winter Thrush,” they cannot thaw. And as we see in the story that follows, “Spring Ice,” when we cannot thaw, sometimes we break. In late August, I said goodbye to my daughter, who’s spending the coming academic year as a teaching assistant in the UK. We embraced, then released each other to our new, separate worlds. As I walked away, I reflected on my gratitude for our love, and rededicated myself to playing my small part in supporting my daughter’s journey. A moment of consecration? Since writing Consecration Pond, I have come to see them all around me.

0 Comments

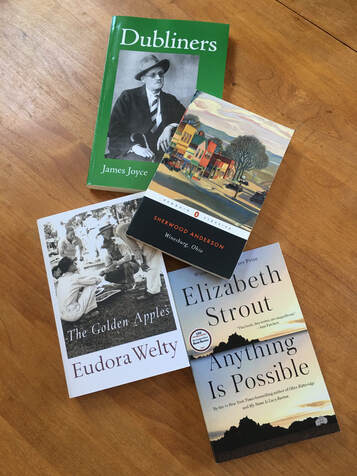

In a recent episode of Maine Calling on Maine Public Radio, Morgan Talty, author of the award-winning 2022 short-story cycle Night of the Living Rez, put in a “shout-out” to the form, characterizing it as an “emerging genre” that might soon merit its own section in bookstores. But what exactly is a short-story cycle? Also referred to as “linked stories” or “a novel in stories,” a short-story cycle is a group of stories that are entirely satisfying when read individually but, because they share characters, themes, or setting, together create an experience of meaning that transcends that of each individual story. In short, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. As Talty points out, short-story cycles straddle the space between the long, deep immersion of a novel and the brief, bracing dip of a short story. They do this by offering the satisfaction of a lengthy engagement with characters, theme, or setting, while unfolding via discrete and quick-to-read encounters that are pleasurable and meaningful in their own right. A moving example is Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried, originally published in 1990, in which the stories relate the experiences of a small group of soldiers before, during, and after their service in Vietnam. Another popular example is Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge, 2008, in which the stories are linked by the presence of—or at least allusions to—the cantankerous Olive. Again, some short-story cycles are based not on characters or themes, but on setting. In place-based cycles, a specific geographical location—a city, town, or smaller community—becomes, in a sense, the main character of the work. Through its residents’ stories, we see that community undergoing conflict and experiencing change leading to a climax and resolving in a dénouement. This is the case with my own novel in stories, Consecration Pond. Above is a photo of a few well-known examples of place-based short-story cycles. Here’s a brief look at each:

I hope this brief look at short-story cycles inspires you to try a few. Even the most devoted fans of the novel are unlikely to be disappointed. For more information on short-story cycles, check out Christopher Marcus' website, linkedshortstories.com.  It's July. Our weather here on Maine's Midcoast has been mild this year, but four days ago, I finally took out my fan. It's 82 degrees out as I write this, and I find myself thinking of the ocean. Perhaps tonight I'll go for a swim. Have you ever gone swimming in the ocean at night? A few years ago, I issued an invitation to myself to do just that. The invitation became this poem, which was published in Off the Coast in the summer of 2020. Night Ocean The tide is out. Enter. The sea is not more cold, more fierce at night. And look-- the waves toss silica and calcium, adorning your shocked flesh with stars. Once you breathed your mother’s brackish waters. Once you crossed a tidal river in your father’s arms. Unfold your limbs and let this dark hour bear you until the churning heavens resurrect the light. I’d written ten linked stories for my collection, Consecration Pond. I even had a publisher. But I had an idea for one more story, with an unconventional—nonhuman—narrator. I’d broached the idea with my publishing team, and they’d all loved it. I’d done my research—books I’d borrowed from my public library and various scientific and historical documents I’d found online. I had a sense of what the story would feel like when it was finished—how it would tie the collection together—but I had no idea how to begin.

What was the basic plot? Who would the characters be? What about theme? Anxiety prickled in my gut as I faced the truth: I was worse than lost—because I didn’t even know where I was going. At one time or another we’ve all been physically, geographically lost. It happened to my daughter and me while we were hiking last spring in Dartmoor National Park. Fortunately, we had a compass and an ordinance map. Without them, what could we—would we—have done? We’d have been forced to rely on our intuition. When I get lost in a short story, essay, or poem, intuition is the backup tool I’ve learned to trust. The question is, how to access it? One thing I’ve discovered about intuition—mine anyway—is that it likes to come out and play at night. So here’s what I do:

When I invited intuition to help me write my “unconventional” story, I’d barely fallen asleep when I woke again with an idea: Take two of the many themes I’d already tried and discarded—and combine them. I jotted down the idea, and when I woke the next morning, found that, during the night, the two themes had begun to gel. I sat down at my laptop and began to write. There was no hesitation, no starting and stopping. Within a few hours, I had a complete first draft. That draft became the tenth and title story in my novel in stories, Consecration Pond. In academic and professional life, it seems there’s never enough time to get everything done. But now it’s the weekend and your goal is to work on your own stuff—that idea for a new story, essay, or poem. You’ve finished the housework, run the errands—and if you have kids, maybe they’re off at a neighbor’s for the afternoon. In short, you’ve got plenty of time. So what’s holding you back?

If you’re like me, the answer is usually self-doubt. As in: “I’m not going to be able to write this. Not the way I want to. Who do I think I am?” Sound familiar? When self-doubt sabotages your goals, try giving it a time-out. Here’s how. 1. Set a timer for one hour. Imagine sending your self-doubt to another room and gently closing the door. Now promise yourself—preferably out loud—that you’ll have earned your self-respect and peaceful rest for the night if you work on your piece at least until the timer goes off—whether or not you produce a single word. 2. Invite the muses to come out and play. If they don’t show up at first, here are some ways to entice them:

3. Keep playing until the timer goes off. If you haven’t come up with anything promising, take a deep breath and congratulate yourself for trying. But I think it’s more likely you’ll have filled that hour with imagery, dialogue, plot points, research findings, and insights that give you a firmer, deeper sense of what you’re after. Or maybe you actually wrote a few paragraphs… before deciding you didn’t like the direction they were taking you. Even so, such passages are useful in demonstrating what didn’t work, and what might—which means you’ll have finished the hour with a place to begin next time. 4. Open the door to the imaginary room where your self-doubt has been waiting. And don’t be surprised if it’s gone. Do you have a strategy for managing self-doubt? If so, share it in the Comments. I’d love to read it. In a 1985 essay called “Not-Knowing,” the writer Donald Barthelme noted that a writer “is one who, embarking upon a task, does not know what to do.” [The Georgia Review, Vol. 39, no. 3, Fall, 1985, pages 509-522] Why? Writing a science textbook is an act of explaining, and writing a news article about a crime is reporting. But writing poetry, memoir, and fiction are acts of creating—starting from the blank page. Creating requires imagining, exploring, without any preconceived notion of what you’re going to find—or to put it more precisely, what’s going to reveal itself to you. To me, it’s a process of paying attention not to my own thoughts, but to the constant “show-and-tell” of the world.

Let me share an example. I’d been working on one of the stories in my collection Consecration Pond for numerous drafts, “listening” to the narrator, Gus, tell me his story. But now I was stuck. Gus had told me what had happened, but he hadn’t told me why it mattered—what the point of his story was. I’d been listening for hours without insight, and now it was late afternoon. Autumn. The sun would be down soon. So I put on my coat and went for a walk. As I walked, I didn’t force myself to think of Gus or try to hear his voice. Instead, I paid attention to the crunch of dry leaves at my feet, the colors of the trees, the nip of the breeze. And then, suddenly, the sound of dozens of Canada geese filled the air. I looked up, waiting, until there they were, overhead, seemingly more than a hundred, filling the sky with their precise and spectacular rows of wings and outstretched necks and their bright, loud sound. I watched until they’d flown out of sight. And in the silence that followed, I knew: Gus had seen and heard them, too. They’d told him—and now me—why his story mattered. I went home and, with this gift from a flock of geese, began again. My lesson? Creativity doesn’t begin and end with me—my unique talent, my focused effort, my solitary mind. As Mary Oliver reminds us in her poem “Wild Geese,” the world offers itself to your imagination. So next time you’re stuck, try this: Close the laptop, put on your coat and shoes, go outdoors, and see and hear the show-and-tell of the world. The process of creative writing generates a mountain of “waste.” We spend years writing a novel or short story, only to lose our way, set it aside, and eventually forget everything about it, even the main character’s name. Or we think we’ve gotten it right, and send it off to one agent or literary magazine after another, only to have it declined, over and over again. In an essay in Poets & Writers [March/April 2022, pages 25-29], the writer Steve Almond describes writing one “wretched” novel after another over “three long decades” until finally completing—and finding a publisher for—his debut novel All the Secrets of the World. How did he do it? By leaping “from atop a mountain of my own failures.”

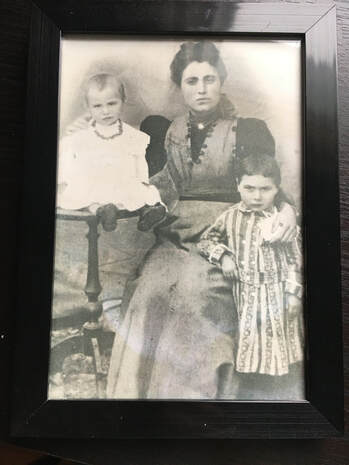

How have I learned to embrace “waste” in my own writing? First, I try to respect all my attempts, no matter the outcome. I think about all the jobs I had—scooping ice cream or answering phones or cleaning houses—before I found a career in publishing that fit. Each job taught me a lesson, even if it was as simple as, “I never want to spend my summer nights pressing balls of stiff, sticky ice cream into wafer-thin receptacles again.” Similarly, there’s a lesson for me in every failed novel, short story, and poem, from a meandering plot to overworked language. Knowing what doesn’t work is important to recognizing—and writing—what does. Second, I consider recycling! Can any part of that story or poem be salvaged, repaired, or repackaged in another form? Last year, when working on my short-story cycle, Consecration Pond, I remembered a story I’d written thirty years ago that included a scene by a pond. It was called “Frogs Like Emeralds.” I’d revised it numerous times over the years, but it still felt underwritten—and now, it was dated. Still, the key conflict between lovers with a secular and a supernatural worldview felt as fresh as ever. So I began again, retaining that conflict but changing pretty much everything else—the characters themselves, the rising action, even the climactic moment. Perhaps most importantly, I changed the voice: Instead of third-person, the story is now told in first person by one of the two lovers, who is addressing—in her imagination—her long-dead but still beloved mother, an element that raises the stakes, giving the story much greater depth and complexity. Now called “Frogs and Goddesses,” it’s the seventh story in Consecration Pond, to be published by Toad Hall Editions in August of this year.  One of my favorite walks from my home in Rockport, Maine is to Lily Pond. It’s a local landmark: the ice from Lily Pond was once so famous for its clarity that it was harvested and shipped throughout the United States—reportedly even as far away as the Caribbean. Four years ago, on April 1, 2017, a light snow began to fall over Lily Pond. This year, it’s warmer— throughout March, the temperature often rose to 40 or even 50 degrees Fahrenheit. But that year, like many years in Midcoast Maine, March was cool, so much of the surface of area lakes and ponds was still crusted over with what we call spring ice. Although it appears strong—unbreakable—spring ice is inherently unstable, usually in areas where a dark mass—a stone or log, for instance—lies beneath the surface of the water, absorbing heat from the sun. Walking on it is therefore dangerous: one never knows when it might break. As I watched the snow fall that morning, something about it—perhaps its gentleness—brought to mind my maternal grandfather, Francesco. He’s the child standing in the photograph above. His baby sister sits atop the little table. His mother, Marta, is the woman in the center. Growing up, I was told only one story of my Sicilian bisnonna, the story of her death only a few years after she immigrated to New York and this photograph was taken. Snow, memory, the darkness beneath the surface of a pond, a lake, or a life… somehow my musings that morning led to this poem. It was published in 2018 in Balancing Act 2: An Anthology of Poems by Fifty Maine Women, from Littoral Books. Spring Ice on Lily Pond Today the ice broke on Lily Pond. Early April yet the snow falls silently as ash from some remote white dwarf star dressing the jagged wound and all the memory of winter. A century ago men cut the ice on Lily Pond with giant blades and hauled it boxed in railroad cars to distant states and cities perhaps Brooklyn carried it in horse-drawn carts to avenues and alleys swanky bars and tenement kitchens one perhaps where Marta mia bisnonna washed the breakfast dishes placed the milk and butter in the icebox knelt and kissed her son and daughter sent them out into the streets and rose alone and felt her numbed heart give way and leaving the door ajar climbed silently the long back stairs and let her cold and shining body fall. Today my mother died her son penciled in a book that I still carry in my memory and page and page as April breaks the ice on Lily Pond.  Today I'm thinking about generosity of spirit. That was a defining characteristic of my brother Brian, shown here at his wedding in 2016. Brian was a VP at a tech company in Silicon Valley, but he found time to volunteer as a tutor to adults trying to learn how to use a computer, to act as a Big Brother to youth, and to serve on the boards of several charities. Within our family, he helped numerous relatives through hard times. In short, he was always ready to share his wisdom, time, and money with anyone in need. My poem about one of Brian's final gifts is called "The Last Shave." Maine poet laureate Stu Kestenbaum reads the poem on the program Poems from Here at Maine Public Radio at this link. The photo above was taken last October, at sunset, by my friend Peter Beckett. It came to mind last night when I heard of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's death. The oranges and yellows, brilliant at the end of day, seem to capture her legacy of empowerment, hope, and even joy. In an article about her life, CNN quoted her as saying, "To make life a little better for people less fortunate than you, that's what I think a meaningful life is." Although she is known for her tireless championing of women's equality, both women and men have much to thank her for, especially her insistence that everyone, including and especially those less fortunate, be treated as equals under the law. Thank you, Justice Ginsburg.

|